This address was delivered at the University of Tasmania on the eve of International Women’s Day, 2017. It has been adapted here for the written medium. The original address can still be livestreamed. Much gratitude is extended to the University of Tasmania.

[20 seconds of silence]

Silence. Many in our communities are silenced and without voice. You see them in your street. A child from a poor, violence-filled background arriving at school without sleep or breakfast, unable to learn. A teenager with a learning disability; he knows he’s smart, but he feels dumb. When people can’t speak out, they’ll act out, and for some, that acting out tips over into crime.

But many of us have not had disability or contact with the criminal justice system, and yet we find that we don’t say things the way we would like to. We might resort to frustration, or using the four-letter words that Australians are renowned for. I want to see communities in which our interactions consistently demonstrate what I call the ‘other four-letter words’: kind, hope, care, love.

If we listened to truly understand the experience of all our people, we could step through our divides with vibrant grace. I’ve spent my entire working life with those whose communication skills are impaired in some way, but I’ve come to understand that unless intentional kindness is in our interactions, we are all impaired, and we impair each other, and we impair our world. Kindness matters. It opens doors for connection with others, and within positive connection, hope grows, and hope is transformational substance which acts upon our mindsets and paves a way to our dreams.

Kind communication enhances everything we already love about who we are as citizens of this country and this world. It has power to transform our contradictions and build our nation.

It is never too late to bring hope to broken lives. Research about what causes people to stop doing crime shows that hope is a major factor. People in prison have offended society in some way, but they will return to community. They can be helped to return with hope, and not with violence. Kind intention expressed in our communication supports new hope, for prisoners and for all of us. And if it’s never too late for prisoners in the trauma of prison, it’s never too late for anyone. Be kind.

To victims of crime, your courageous voices are bringing change, and those voices are needed to continue the change towards the safest and fairest society we can be. Thank you for your bravery.

To men and women in prison I say, don’t give up on your dreams; for more and more, it is understood that so many of you were also victims in your childhoods, but it’s never too late.

And to all of us, be ready always to be kind. We don’t know the roads that others have travelled in their pasts; we don’t know the burdens that they’re bearing in their innermost beings. Kindness is balm and salve.

There are three steps to kind communication. Step one: be kind in your next interaction. Step two: reflect on this. Step three: return to step one and repeat.

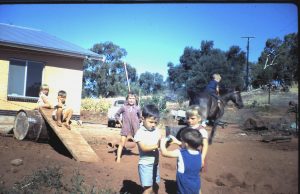

When I was a child – at around age six or seven – I was aware that wars were taking place in the world, and it frightened me. I remember talking with my mum about this fear, and she would say, “Oh, but wars are not happening here, and it’s very safe” – and on the little farm on which I grew up in South Australia, it was very safe.

But knowing this didn’t change that I went to bed each night and thought about the fact of wars happening, and the devastation caused to people and loss of life, and the violence of it all.

This was obviously quite formational for me, and made impact, given that I still remember it these many years later. There was an associated mental image that I regularly went to bed thinking about. In childlike imaginings I saw what I thought was a classic battle scene – tanks and soldiers lined up on one side, and on the other side: facing each other. And there was a child in the middle, and I think that child might have been me, and I was calling, “Stop, don’t do this. Why don’t you just be kind? Let’s all be kind”.

Obviously now as an adult, I recognise the childhood naivety of such thinking. And yet there’s a part of me that doesn’t want to give up on those sentiments as naivety – for how can we expect to prevent violence writ large in our worlds when we don’t choose against violence writ small within ourselves?

Kindness is one of the responses that we can choose, against the violence writ small within ourselves.

A few years later, at about age nine or ten, I recall a childhood shopping expedition with my mum. It was in the summer holidays, and we’d gone into the local town to buy the fortnight’s supply of groceries. Mum was chit-chatting with the person on the checkout; but I didn’t know this person. I came away from that interaction asking her, “Who was that? Do you know that lady?”. And she said, “No, no, no, I don’t know her”; and I responded, “Then how come you were talking to her all the time?”. To which mum said, “Well, it’s nice; it’s nice to chat to people. It’s good for us, it’s kind, and it makes us all feel good”.

And again, I think that this was one of those transformational moments for me as a child. It taught me of a simplicity of being connected with the people in my space right in the moment; and for any of us, being connected with the people in our space in any one moment.

Just before I went to Canberra for the Australian of the Year Awards, I was talking with my mum. She said, “Rosalie, this is amazing! That you are in this position! Oh my gosh!” (and certainly I had oh-my-goshed to myself many times before this conversation with her). And she went on to say, “I think if there’s anything that you bring to this – whatever happens in Canberra – I think what you bring is your ordinariness”.

Bless her heart.

And actually, I agree with her completely. For we all, in our intentionally-lived ordinariness, have the power within our grasp, within our reach, within our next interaction, to do a small something that can create a ripple that changes our world.

Now, it’s obviously not going to be changed all in a moment; but the intentionality to be connected with and kind towards our fellows is powerful.

So, there remains a part of me which wants to hold on to that childhood hope. Because I believe kindness has that much potency. It is other-minded benevolence.

We’re so sophisticated now, I’m so conscious of that, and yet how much of our sophistication is wasted on mitigating the results of not having been kind? There’s a progress-halting equation going on there; and it’s one that I think is worth reflecting on.

I want to read a piece of poetry to you. It’s called Blackbirds, and it’s written by Julie Cadwallader-Staub, an American poet. She writes:

“I am 52 years old, and have spent

truly the better part

of my life out-of-doors

but yesterday I heard a new sound above my head

a rustling, ruffling quietness in the spring air

and when I turned my face upward

I saw a flock of blackbirds

rounding a curve I didn’t know was there

and the sound was simply all those wings

just feathers against air, against gravity

and such a beautiful winning

the whole flock taking a long, wide turn

as if of one body and one mind.

How do they do that?

Oh, if we lived only in human society

with its cruelty and fear

its apathy and exhaustion

what a puny existence that would be,

but instead we live and move and have our being

here, in this curving and soaring world

so that when, every now and then, mercy and tenderness triumph in our lives

and when, even more rarely, we manage to unite and move together

toward a common good,

we can think to ourselves:

ah yes, this is how it’s meant to be.”

In regard of my childhood hope – and with great respect to the poet whose words I love – I would love it if that piece of poetry spoke its truth without needing the words “every now and then”, “even more rarely”, and “we manage to”.

In the words of beautiful Mary Oliver, wonderful poet - if you don’t know Mary’s work, she writes like a songbird - “I believe in kindness. Also in mischief”. And in the interest of disclosure, I must say that I too believe in kindness, and also in mischief – although mischief I like to call playfulness: playfulness is kindness plus fun!

In sharing these words, I am presenting as a clinician. I’ve had more than 30 years’ experience working as a speech pathologist. I’ve worked clinically across all of that time. I’ve seen hundreds and hundreds of children and adults and teenagers across my little table – or slightly bigger table. I know that to build-in the skills of communication, when those skills are missing, requires just keeping on at it – grafting and grafting and grafting. Helping that person to learn, giving them experiences of being tenacious, staying with them, encouragingly, knowledgeably and tenaciously in the learning tasks and reflections.

The reality of many speech therapy tasks – and I tell my clients this as well – is that the process could be boring. But because as clinicians we know this, it is in fact our job to make it engaging, fun and enjoyable for the client. And we have to give them a way of seeing the end from the beginning – of knowing that there’s a trajectory which we’re intentionally following. And kindness is one of the most important clinical tools for accomplishing all of this. It’s one of the most important clinical tools to use with the client in the therapeutic experience. It’s also one of the most important responses to lift-up to the client, so that when he has made a kind response, that the honouring within that responding is acknowledged, celebrated and reflected on. This is particularly so if the client has a social communication difference of some sort. He is given a moment to notice his own associated feelings, as well as the responses of others; and to reflect.

I would like to share a further couple of stories to illustrate some examples of this, as they might happen in the clinic.

The first is a recent story of a little girl with autism aged five or six – a clever little poppet with lots of language that you can check over here in this post. She was using the swing in the clinic room in a way which was a little bit dangerous, and I said to her, “You know, mummy and I need you to use the swing this way, because we’re worried that you might end up having a crash – so swing like this”. And then mum and I went back to our conversation, and just a couple of moments later I looked across, and I saw the little one preparing to swing dangerously; but then I saw her facial posture shift – an indicator of her changing her mind; I saw her glance across to her mother and I, and then sit back and swing the safe way.

So, I moved across to her, and said, “Oh my gosh, you were so kind. I saw what you did. You were thinking about Mummy and I – that was kind. You were thinking about how it was going to be for us, you didn’t want us to be worried – you were kind to do that.” And as she listened, I saw an expression whiz across her face, belying a transformational moment. It showed me plainly that the word, “kind”, had landed to her in an affectively powerful way – a deeply, emotionally powerful way.

Another story, something similar. A little boy with autism of around age nine or ten. One of those dear little people whose presentation of autism resulted in him coming across as if he were rude and arrogant. Now, he was actually not rude, and he was not arrogant, but his manner of use of his communication skill would usually mean that others would pick up on his cues as if this were the case.

These little poppets can have a particularly hard time making friends and fitting in. I have too-often heard other people use the words “rude” and “arrogant” about these children. It’s my job to help them show that they are not; that they are seeking to engage. I have many times said to the younger clinicians that I work with, and to teachers, teacher assistants and various others, that our job is to like the kid! We’ve got to find that little jewel inside the child and hold it up to him so that he can also see it – that he might grow thereby: grow in the light of it, actually. And so I’ve often said, “If you don’t like the kid, like the kid!”. It’s an imperative in my trade.

Returning to the story, this little chap and I were playing a game, and he was throwing the pieces at me instead of passing them to me; and I was picking them up. And I noticed that I began to feel a resentment rise within me. But I have learned that whenever I feel that as a clinician, that I must heed it as an important ‘note to self’. If I am feeling resentful then I am at-risk of not ‘liking the kid’, and I must take control of myself and respond in a way which enables the child to learn about the skill that I am seeking to help him grow.

And so, he was throwing pieces at me, and I’d said to him, “Oh, it makes me feel bad when you throw the pieces at me like that. You know, what I’d love is if you could pass them to me like this. That would make me feel really good. That would be kind”. And then, whilst the next piece was still thrown at me, he didn’t throw it quite as roughly. And so I picked-up on this and said to him, “Oh, I noticed then, that you were really kind to me. You shared that piece with me. That was wonderful; it was kind”. On the face of it, it might not have looked kind – but I knew how much effort it had taken him to modify his response in just this small way. And it was effort worthy of acknowledgement, reinforcement and lifting before his eyes.

The events of this story took place many years ago – they were amongst many early, transformational and unforgettable experiences for me as a clinician: they helped me realise the potency of the affectively-formational word, ‘kind’.

What happened was this: in the moment that I thanked this little boy for being kind, he looked at me, and did a double-take – he looked again – he smiled at me for the first time, looked deeply into my eyes and we both experienced a moment of connection in which we each saw and experienced something fundamentally human, and worthy, in the other. At that point there was a shift in his gentleness – it was because I had seen in him something that typically didn’t get seen, and I had responded to it. Kindness. Other-minded benevolence. It is powerful.

I have two more stories. I want to share something that a young woman from one of our prison programmes said to me. My charity, Chatter Matters Tasmania, has been running the world-respected Circle of Security parent-child attachment program in the women’s prison in Tasmania. It teaches, in this case mums, to become attached to their children such that the security of attachment in the child is supported and grown. It supports the mental health of both parent and child, in case there is a situation where this relationship is disrupted you can get help and it can really shift and change the opportunities that that child will have in his future, if he can be securely attached with his mum.

Whilst teaching this program a mum who had come in a little late to the group on this particular morning said:

“To tell you the truth, I’m having a pretty shitty morning, and I didn’t want to come up here today. I felt like crap, and I’m crapped off with this place. But then when I came in, I saw you give me this big smile, and you said, ‘How are you?’ And you was kind, and I noticed it made me feel better. Then I felt ashamed that I was so crappy, and I’m glad I come up, because it’s made me feel good, and I realise that I don’t have to feel crappy – and I want to be kind like that too”.

She told me this in the morning tea break, but she’d had the experience when she first arrived into the room and I had welcomed her. In that moment, when she had arrived into the room and we had had that interaction, I had witnessed the transformational moment pass across her face. Kindness can make that difference.

The guys I teach in prison thank me for working with them on their reading and writing skills – but more than anything, they thank me for being kind. ‘Kind’, is the word they have experience of, that they feel, that they relate to. One of the guys recently said this, “Rosie, respect. I hope one day there’s a 50-letter word in the dictionary describing people like you”. What he meant was – and this was about kindness – that a 50-letter word would have to be better because it would be a really, BIG word – making it ‘better’ in his mind. If it’s bigger and harder to spell, it therefore has to be better!

But actually, what I find, is that the four-letter words do the job just fine.

I want to see families grow – and also workplaces, encounters with strangers in our public places; a world in which our interactions consistently demonstrate the ‘other’ four-letter words: kind, hope, care, love.

Some beautiful scholarship has recently emerged from the University of Tasmania about kindness. Daphne Habibis, Nicholas Hookway, and Anthea Vreugdenhil last year had an article published in the British Journal of Sociology. The definition of kindness which they used was ‘an authentic caring response to the call of the other’. They’ve summed it right there – that’s what kindness is. It is other-focused, tender, benevolent, generous; and of course, it also involves some action. Interestingly the Habibis et al study showed that women are significantly kinder than men.

And here is a final story. It’s a story about some young friends who came and stayed with my husband and I after the Falls [music] Festival. The essence of this story raised consciously for me some deeper ponderings and yearnings about the power of kindness, and about its intentional actioning.

What happened is this. On the first of January in 2016 my husband and I had five young people come and stay with us after the Falls music festival – just for one night. They just needed somewhere to crash. We already had a family of five staying with us, so all the bedrooms were full; but our young cousin had rung and asked to stay, and of course we wanted to see her – we love her – even though we knew she would just be breezing through for a night with all of her crowd. Now I’ve raised boys through the Falls Festival days and so I knew exactly what that crowd were going to turn up like – and they certainly did – they were hung-over, dehydrated, tired, hungry, sun-burned. And so anticipating this, Richard and I had prepared a room which we have out the back and had laid mattresses all over it, and I had ice water ready for them – with lemon – when they arrived; and I pointed them at the showers and gave them clean towels . So they all came traipsing in, and we said, “right, here is all the stuff that you need”; and they used all the stuff – and then they went to bed.

That was at about midday. And it was at about 7:00 o’clock that evening that they got up for dinner – it was such a typical post-Falls day. Now I’d particularly prepared dinner for them because we wanted to spend the evening with them once they were refreshed, because they were heading off the next day. And because it was the first of January, conversation during the evening turned to New Year’s resolutions. And it eventually swung around to my turn, asking about my New Year’s resolutions. I don’t always make such resolutions, but in this year, I had. And so I shared with them. I said “I want to be more kind”.

At this, one of our young guests almost choked on his mouthful of beer. And his response was “How is that even possible?”. They had just had every need met, and here they were eating this great dinner! But I affirmed that I was serious. And said “I know that it is possible because I am aware that sometimes I might do things that people receive as kind, but if I’m not present to them as I do those things, if I don’t give myself to them in presence, then I don’t think I’m being as kind as I want to be – it is the presence that I want to improve in”. And my friend from the other family of five that was staying with us, burst with “See, she’s even thought of that!”.

Expression of these two points of surprise from my guests, triggered surprise in me; and caused me to think that the presence in kindness was worthy of further reflection. To have arrived at the New Year’s resolution, I’d obviously already been thinking about this over the preceding few months; reflecting that it is possible to do kind actions from a genuine place of other-mindedness, but nevertheless without being fully present to the other person whilst doing so. I had concluded that without attentive presence to the wholeness of the ‘other’, that kindness might not reach the zenith of the power which it holds for shared good. My interests lay in the processes of being communicatively more deeply connected with other people, the creation of mutually enjoyed reciprocity, and honest, problem-solving listening; and the roles which each of these have toward increased social justice.

It is always clear to me that in the clinic I need to be fully, attentively present. There is no other way to serve my clients in accordance with their best interests. In the clinic, kindness is a strong, essential tool.

The New Year’s Day conversation left me thinking once again about the social power of kindness beyond the clinic walls. I recognised that I could comfortably use and talk up kindness in the clinic, and yet feel like I need to make excuses for its social power beyond the clinic walls. This became a point of important reflection and self-examination for me. In fact, I had somebody say to me as I was preparing a Facebook post to promote this very presentation this evening, “Don’t just say you’re talking about kindness. No one will come. It will sound too weak”.

We seem to broadly, and unreflectedly, hold within our society a notion that kindness is somehow weak. In the clinic, I’ve found it never to be weak; I’ve found it only ever to be strong.

This then, is one of the key points which I wish to lift before us all this evening – we hold an unreflected notion in our society that there is something weak about kindness. But on the eve of International Women’s Day – when we have learned a little from research that women tend to be kinder than men, and will find kindness and opportunities for kindness more frequently – I wish to counterculturally lift kindness as a response-choice which is incredibly courageous.

Over history, kindness has been diminished as something of an adornment of women (Philips & Taylor, 2009). George Saunders, American author, said this: “What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness”. And so many people reaching the end of their lives, and reflecting on their lives, say similar things. Let’s acknowledge this now, while we’re living in this soaring, curving world.

These reflections on kindness were brought home to me strongly, again, six months ago. I was presenting to a group of policy makers about communication skills; and about how important it is for highly competent communicators to understand that many people have communication skills which are lower on the spectrum of ability. I was highlighting that a different compassionate engagement is needed from the more competent communicators, so that those with weaker skills are supported, but not patronised. I was asked this question, and it was a very good question, but it put me on the spot: “If you could tell us just one thing that we could do to be better at communicating with this particular cohort whose communication skills are weaker, what would it be?” And the first thing that popped into my mind in response, was “Be kind”. But I second-guessed myself, thinking, “I can’t say that, it’ll sound too weak to a group such as this”. Kindness lies in actions which arise from the inward state of benevolent other-mindedness. This is a source of motivation for many actions, but the objectively observable actions which emerge as kindness can take many forms – not all those forms, however, are objectively representative of kindness in all situations.

So there I was, in the back of my mind I was racing – all the while trying to look composed on the front of me(!) – racing to apply logic and priority to the distillation of just one key communicative response, for there are in fact a raft of responses. Inwardly, I was searching for an objectively observable behaviour to name up; one which is highly-associated with kindness in all its possible presentations. This conversation with self was happening behind the exterior of calm: “What are the outward, observable manifestations of kindness? Which of those behaviours most consistently demonstrates the intent of kindness?”.

Smiling, of course, is one of those behaviours; and so I found myself responding with, “Smile”. Well, I’m not sure that I gave a powerful answer to the question!

This event was formative for me. I was completely slapped in the face by the dissonance I immediately experienced within myself in making that response in that context. It was a step-down from that value which I know to be so extraordinarily (yet ordinarily) connecting, ameliorating, empowering and restorative – kindness.

I’m not going to make that mistake again. And so on the eve of International Women’s Day, this day upon which we are celebrating women, celebrating their achievements and contributions, I particularly want to say that this is a group – we women are a group – who have a head start on raising and powering this virtue. Which people yearn for. Which all people yearn for. And which the world needs if it is to bridge the divides we people have created within it.

But I don’t mean that we women have the jump in order to continue this unreflected narrative about kindness as an ‘adornment’ of women. I don’t mean that at all. I mean, rather, to emphasise that kindness is courageous.

Unreflectedly, men, over the centuries, have dominated in the idea of courage. There is a plethora of “princess and dragons” stories upon which we are raised (in western culture) – men courageously taking their vulnerable, grillable bodies into the tower of a fire-breathing dragon to rescue a princess. But courage does not have to be a super-human, death-defying act of fairy-tale proportions. It is simply about vulnerability; and following one’s heart in the presence of vulnerability. It’s about noticing that something is fearful to one; and then going through it anyway – continuing through the fear, recognising the vulnerability.

Joseph Campbell said this in The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

“The world’s great heroes are mere human beings who broke past the horizons that limited their fellows, and returned such boons as any man [or woman] with equal faith and courage might have found”.

So, courage exists, equally, in the ordinary. The English word ‘courage’ comes from the word the French word for ‘heart’, and it means ‘being motivated’. And I think this is the courage that we ought to lionise, rather than that other fairy-tale notion: because looking into another human being is vulnerable territory – it is a thing of courage; offering oneself in tenderness and benevolence to the vagaries of another human being is vulnerable. These things take courage.

And similarly, looking honestly into oneself is vulnerable territory. This is also a thing of courage. I’m going to read a quote from the book Teaching a Stone to Talk by Annie Dillard, an American author. I like these words because they link that unreflected masculine notion of courage with the honest look at inner self. This is worthy consideration for all of us – reflecting on what courage is, and what kindness is. They arise from people. They are not about men or women. They are about people.

Annie Dillard wrote:

“In the deeps are the violence and terror of which psychology has warned us. But if you ride these monsters down, if you drop with them farther over the world’s rim, you find what our sciences cannot locate or name, the substrate, the ocean or matrix or ether which buoys the rest, which gives good its power for good, and evil its power of evil, the unified field: our complex and inexplicable caring for each other, and for our life together here”.

There are some intellectual problems with kindness. If people are interested to read about some of these problems, Adam Philips and Barbara Taylor’s On Kindness is a really great little read.

In ‘Speechie School 101’, we learn about receptive and expressive language. Receptive language is the language we understand when it is spoken to us; expressive language is the language we use ourselves. As kindness involves other-mindedness – being aware of other and being mindful of other – then I would just like to put to you that respect is like a receptive version of other-mindedness. Parsing the word – ‘re’: again; ‘spect’: to look – we see that when we respect somebody, we are invited to ‘look again’, and to see in them those qualities of intrinsic worth which we might not have seen at first glance. We see their humanity. That is respect. To see and understand the intrinsic worth of another. That is respect. Respect is a change in the one doing the looking. It is an intransitive verb indicative of the inward state.

But kindness involves action: action which is motivated by that same other-mindedness; action going outward from one person to another. Kindness is the positive, expressive version of other-mindedness. Receptively and expressively, we can think of respect and kindness as partners of each other.

Other-mindedness is the absolutely necessary stance of the clinician in my field. It’s also the absolutely necessary stance of the criminologist. What I’m wanting to elevate in this talk is how much I would love to see other-mindedness become the absolutely necessary stance of our culture – respect and kindness.

Kindness cuts through the craziness. It cuts through the crises. It cuts through the crap. Be ready to always be kind.

There are three steps to kind communication.

Step one: be kind in your next interaction. The joy of kindness, and the discovery of its power, are in participation. It’s not complete in mere intellectualisation of it. it is complete in operationalisation. Doing kindness, being involved in kindness, receiving kindness. Participation dissolves the intellectual challenges. The joy and discovery of the power of kindness are in participation. It’s “better felt than tellt”. And there’s another expression which I love, which arises from our clinical work: “there’s magic in the mess”. The poets have known this for years. Jack Kerouac wrote: “Practise kindness all day to everybody, and you will realise you’re already in heaven now”.

Here are some of the actions of kindness:

- Smile

- Make warm eye contact

- Welcome

- Greet/Farewell

- Ask-Listen – open-honest questions

- Politeness words

- Warm tone of voice

- Apologise readily

- Be with

- Gratitude

- Playfulness

Simple as these may seem, the bringing of intention to these actions in interaction with others demonstrate benevolent, tender other-mindedness, and therefore display as kindness – and can be transformational.

And step two: reflect. Reflect on what you noticed in acts of kindness – what did you notice in others, what did you notice in yourself? John Dewey, American educationalist, said: “We don’t learn from our experience, we learn from reflecting on our experience”. It is in reflection that transformation begins. In similar vein, and beautifully, Mary Oliver has written: “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work”. In another place, she writes: “Love yourself. Then forget it. Then, love the world”.

We can expand ourselves and each person around us by kindly holding and raising their courage through relationship. To do this, we need first to notice. Let’s look back on some of the key words of the young woman I mentioned earlier who had had a shitty morning but who came up to the parenting program anyway. She said, “You was kind, and I noticed it made me feel better.” This was a transformational moment. She noticed. So she was thinking about what had happened in her processing system. “It’s made me feel good, and I realise that I don’t have to feel crappy”. She realised. Transformational moment number two. We need to notice. Being other-minded and making choice and change for other-mindedness must include our intention.

And then, of course, there’s practice. This is the step three: return to step one and repeat. For an occasional virtue to become a deeply embedded value that one never wavers from, it is practice which is required; and reflective, contemplative practise of some sort. Now, for some people, that might be mindfulness with its loving-kindness; it might be prayer; or other types of meditations; reading, cloud-gazing. My latest favourite is running in the wet sand on the beach and watching the patterns in the water as it rolls back. That’s captured me just lately. Rhythm, beauty, largeness – which are largesse. Some version of contemplative practice is helpful – for it grounds us. It is supportive in stabilising our capacity to respond, rather than to react. It gives fortification to make the choices which we would wish to make in the heat and distraction of the moment.

So, on the eve of International Women’s Day, I want to quote Oscar de la Renta, who said: “The qualities I most admire in women are confidence and kindness”. But then I want to immediately paraphrase him and say the qualities which I most admire in people are confidence and kindness. We women may have the jump on the latter, and there is unreflected narrative in our society that men have the jump on the former, the confidence; but for us all – for men, women, people – we can both talk-up, and seize, courage – and kindness. These virtues don’t belong to one of the sexes or the other, or to the genders. These are about our humanity.

For mine, I have made a choice that I’m not at any point going to find kindness weak in the future. It is strong. My encouragement to you is ‘be kind’. Be very kind. Be courageously kind. Be implacably kind. Be fiercely kind. And reflect. And then return to step one.

Philips, A & Taylor, B (2009) On Kindness, Penguin Books, London.

Hi Rosie, an inspirational talk. I loved it. Warmest wishes, Cate.

Thanks so much, Cate! Kind of you to stop by and say so 🙂

Warmth right back atcha…

Rosie

Prem Rawat says – if you want to be strong, be kind. ????

Beautiful, Irene – thank you. He’s a very fine thinker and influencer. Thanks for sharing.